In this blog Robert Thomas considers delays in immigration appeals and available data.

There have been some news stories over recent months about delays in immigration appeals. In December 2016, Meg Hillier MP, chair of the Commons Public Accounts Committee, said that the immigration appeals system was on the verge of a crisis as a result of the delays that continue to plague the process. According to Hillier, the current state of the immigration appeals system was ‘shocking’: ‘The response of the government has been pretty poor and it is having a devastating impact on people’s lives … People are coming to my surgery who have not heard when their case will be or have been told to wait months.’

In December 2016, before the Commons Justice Select Committee, the Minister for Courts and Justice, Oliver Heald MP said, in response to questions from Keith Vaz MP, that HMCTS was putting an extra 4,500 days of tribunal time into this area to try to speed things up. In February 2017, the Law Society Gazette reported that a rapid decline in the number of immigration tribunal judges could herald a crisis, despite the government’s insistence that there is sufficient capacity to deal with a growing backlog of work. According to Christopher Cole, a member of the Law Society’s immigration law committee, ‘The most common and frustrating issue has been the late adjourning of hearings due to a lack of judiciary. Delays in the first-tier tribunal (immigration and asylum chamber) have been pretty extreme over the last 18 months or so.’ These reports followed an early report from the Free Movement blog back in July 2015 that delays in immigration hearings were allegedly being caused by a funding dispute between the Home Office and the Ministry of Justice.

The purpose of this blog is to consider the available data about these developments. This tribunal jurisdiction has been subject to much change and upheaval over recent years and such change is likely to have affected the timeliness of appeals. The data are taken from the MoJ’s official tribunal statistics and the judicial diversity statistics. By examining the data, we can shed some light on a key issue in any decision-making system: the relationships between the number of decisions to be made, the number of decision-makers, and the amount of time taken to make decisions.

The number of appeals

First, the number of decisions to be made. Figure 1 shows the number of appeal receipts, that is, the incoming caseload, the number of appeals decided, and outstanding appeals. There is a clear downward trend in the number of appeal receipts and appeals decided. This is in line with legislative changes such as the withdrawal of appeal rights under the Immigration Act 2014.

However, a crucial point to highlight in Figure 1 is the gap – a – between the number of appeals decided and outstanding appeals. The number of in-coming appeals has reduced, but there is still a large number of outstanding appeals waiting to be listed, heard, and decided. In October to December 2016, the First-tier Tribunal (IAC) decided 14,620 appeals, but there were nearly four times as many outstanding appeals –some 57,954 - waiting to be heard and decided.

Table 1 shows the difference between the number of outstanding appeals and the number of appeals decided since Q4, 2014-15.

The obvious implication is that there is a considerable volume of outstanding appeals waiting around in the system. The ability to clear such outstanding appeals depends largely upon the number of available Immigration Judges.

The number of Immigration Judges

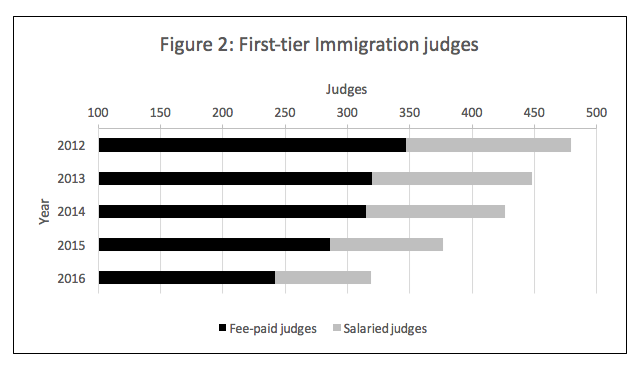

What then has happened to the number of Immigration Judges? As Figure 2 shows, the number of judges has been reduced by a third from 479 judges in 2012 to 319 judges in 2016. The proportion of both fee-paid and salaried judges has reduced by 30 per cent and 42 per cent respectively. It is to be expected that the number of judges would decline in line with the reduced number of appeals. Nevertheless, the number of outstanding appeals does raise the question as to whether the reduction in judges has been too large and taken place too quickly given the outstanding caseload.

Timeliness

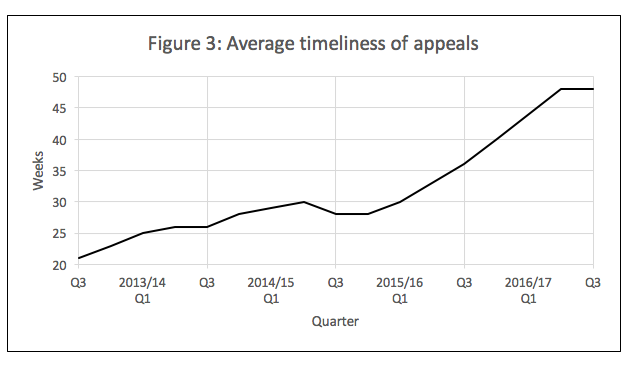

What then of timeliness? The timely hearing of cases involves a balance. If cases are decided too quickly, then there is the risk of rushed and unfair justice. On the other hand, justice delayed is justice denied. The above trends – increased outstanding appeals and reduced numbers of immigration judges – have obvious implications for the amount of taken to hear and decide appeals. As Figure 3 shows, the average number of weeks taken to decide appeals has more than doubled from 21 weeks in 2012/13 to 48 weeks in 2016/17, and the average length of time taken to decide all immigration appeals is now nearly a year. The data presented here provide the mean average. There will be outliers of individual appeals taking less and more time to be decided.

This figure shows the average timeliness for all types of immigration appeals. It is also possible to break down the figures for particular appeal categories. Figure 4 shows the average timeliness of entry clearance appeals, which has more than doubled from 38 weeks in the fourth quarter of 2014/15 to 83 weeks in the third quarter of 2016/17. These appeals typically concern a relative who wants to join their family already present in the UK. The success rate of such appeals varies, but it has regularly exceeded 40 per cent. In other words, a sizable proportion of individuals who ultimately succeed in their appeals have been waiting longer for their appeals to be decided.

It might be expected that an increase in the amount of time taken to decide cases would be the inevitable consequence of an increase in the number of appeals being heard and decided. However, the number of appeals being decided has actually fallen as Figure 5 shows. In quarter three of 2014/15, the tribunal decided 2,791 entry clearance appeals. Two years later, it decided only 840 such appeals. In other words, during a period in which the number of appeals being decided has dropped, the amount of time taken to decide appeals has increased substantially.

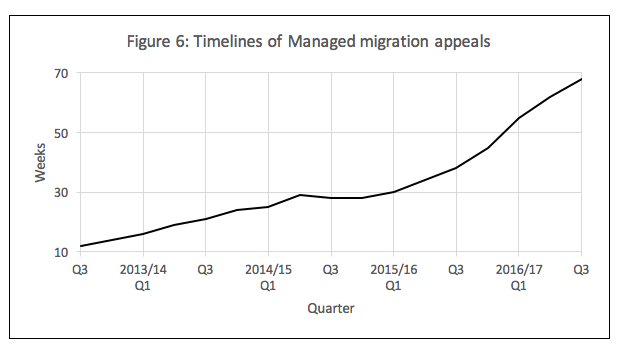

There is a similar trend in relation to managed migration appeals. The number of appeals being decided has declined, yet the time taken has increased. The average timeliness of such appeals has more than doubled over the last couple of years (see Figures 6 & 7). Again, the success rate of managed migration appeals has regularly exceeded 40 per cent.

Both entry clearance and managed migration appeal-types were withdrawn in 2015. Accordingly, it might be assumed that such appeals were no longer treated as a priority. However, delays have also affected new appeal categories. For instance, human rights appeals were introduced under the Immigration Act 2014. In the first quarter or 2016/17, the average amount of time taken for such appeals was 24 weeks. In the third quarter, it was 45 weeks.

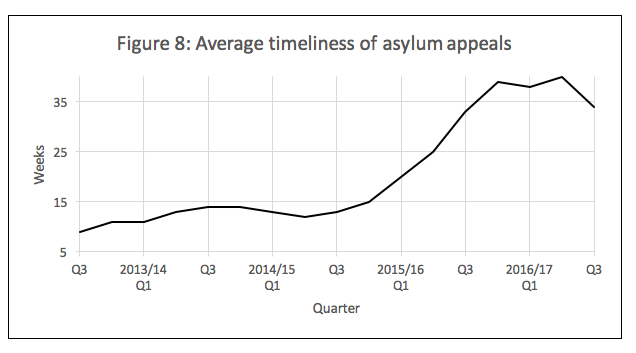

Another development has been the increased amount of time taken to decide asylum appeals. In the past, there has been an intense focus on the timeliness of asylum appeals. Yet, the average number of weeks taken by such appeals has almost quadrupled from nine weeks in Q3, 2012-13 to 34 weeks in Q3, 2016-17 (Figure 8). The number of asylum appeals decided has varied over time with reductions and increases. Nevertheless, there is a legitimate interest in the timely determination of such appeals in terms of both the public interest and the need to afford international protection to refugees.

Overall

The issues of the volume of cases and time taken are not unique to immigration. Delay is an inherent evil afflicting all types of litigation. There are volumes of outstanding appeals in other tribunal jurisdictions. There is also a major issue concerning the number of immigration appeals going from the Upper Tribunal (Immigration and Asylum Chamber) to the Court of Appeal and whether the current arrangements are sustainable.

There are various causes of tribunal delays in immigration appeals. The government has said that the increase in average time taken for cases to be cleared is due to an increased proportion of more complex cases which require more court time. Anyone might be forgiven for not accepting that unqualified explanation. After all, why have immigration appeals suddenly become more complex when many such previous cases were relatively complex?

Other causes of delay include the behaviour of the litigants. The parties to an appeal can request adjournments. Furthermore, workload fluctuations can create sudden and unpredictable increases and then decreases in appeals, with consequent implications. However, if the number of judges was cut in anticipation of a reduction in the number of appeals following the implementation of the Immigration Act 2014, then the current delays may be in part caused by a lack of planning or foresight about the likely number of incoming appeals following the transitional nature of those changes. In some cases, the reduction in the number of Immigration Judges has prompted the adjourning of appeals simply because there is no judge available.

Whatever the precise cause, there are legitimate concerns that people who have been exercising their statutory rights of appeal are experiencing unnecessary delays. There is also a wider public interest in the timely determination of immigration appeals. Immigration is a notoriously political issue. In practice, appeal delays adversely affect both immigration control and letting immigrants who qualify into the country – it cuts across both sides of the political debate. Irrespective of the political dimension, such delays pose risks to the legitimacy of the process and trust and confidence in it.

Looking to the future, JUSTICE is currently undertaking a project into immigration and asylum appeals. Further, the HMCTS digitisation project is also in train. Nevertheless, the gap between outstanding appeals waiting to be heard and the number of appeals currently being heard and decided is considerable and needs to be brought under control.

About the author:

Robert Thomas is Professor of Public Law at the School of Law, University of Manchester.

Further reading

For two books by former Immigration Judges, see Geoffrey Care’s Migrants and the Courts: A Century of Trial and Error? and James Hanratty’s The Making of Immigration Judge. For an academic study of asylum appeals, see Thomas, Administrative Justice and Asylum Appeals.

Discussion

Trackbacks/Pingbacks

Pingback: Immigration appeals and delays: On the verge of a crisis? | Martin Partington: Spotlight on the Justice System - May 18, 2017